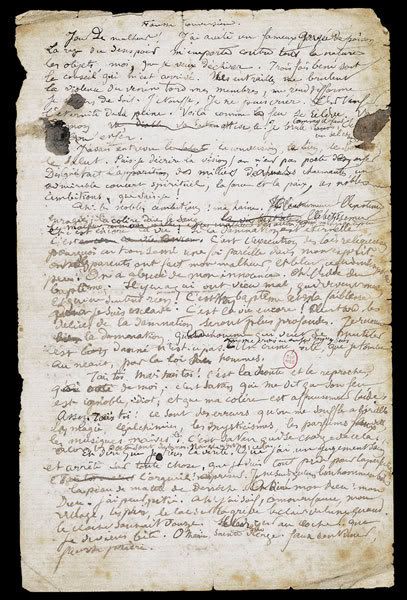

Most of this is, of course, pure fantasy, as is the still-repeated legend of his return to his mother's house after Season's publication to burn every copy in the fireplace, as supposedly witnessed by his horrified sister. Most of the print-run he commissioned survived, as did a few of the manuscripts. Their numerous drafts show us a very deliberate and painstaking act of composition and a mind in complete possession of its faculties.

This was not the farewell to writing that it so fittingly appears to be. Rimbaud was not known for long goodbyes, and as Graham Robb writes, "The sheer biographical convenience of this scenario makes it deeply suspect. Literary works do not queue up patiently, waiting to write themselves into the chronology. The prose poems of the Illuminations overlap Une Saison en Enfer at either end."

Within this dense and elusive text we find a multitude of voices: a Faustian hustler who has finally been called to account for his debts; an illiterate savage caught in the juggernaut of colonizing white men, forced to submit to their clumsy attempts at edification; a cruel and careless "Infernal Bridegroom" trailed through the underworld by his long-suffering "Foolish Virgin"; a sinner begging forgiveness from a God he renounces in the same breath; a poet, who may or may not be Arthur Rimbaud, recounting his own history and that of his ancestors, finding them all, and himself above all, wanting for any redeeming qualities.

These voices may be read as allegories, brutal fables summarizing what it is to live in a state of disconnection from oneself, without a sense of direction, suspended in a sort of nihilistic purgatory. In this way they are "absolutely modern", as Rimbaud demanded of them and himself. Their cacophony echoes our own inner disputes, and how they bleed out into society at large. We cannot escape their grip, or their questions, as Rimbaud himself was well aware:

One of the voices,

always angelic,

--it was talking of me--

Sharply expressing itself:

--and Rimbaud's questions, what the voices say after the pregnant pause of that colon, remain relevant to us in ways even a self-proclaimed seer might not have known.

Rimbaud asks six questions in the section of Season titled "Bad Blood":

To whom shall I hire myself?

What beast should I worship?

What holy image are we attacking?

Which hearts shall I break?

What lie must I keep?

In what blood shall I walk?

Questions as singular as these surely deserve thinking about. So I'm going to do just that, using the allegories I find in my deck of cards and its own multitude of voices.

No comments:

Post a Comment